Dribble castles, only inches tall

Dribble castles, only inches tall

Category Archives: Death

Writer’s Fourth Wednesday

I’m posting a piece that I wrote for a Memoirs class in November of 2011 for Victoria Slotto’s prompt, but before I do, I must post a joyful Happy Birthday message to my daughter, Emily!

Happy 23rd, Baby Eyes!

On the day she was born, it was pouring rain in California and CNN was reporting the end of the Gulf War. Does that mean she’s special? Well, of course!

Okay. Now my memoir piece. Not surprisingly, it is visual-heavy.

Sluggishly wiping the drool from the side of my face, I rose from the floor and went down the hall to look in on Jim. He was not in our king-sized bed. I found him in the master bathroom, weak and sweating. He was sitting on the mauve vanity chair, his massively swollen torso slumped over the toilet. He had been throwing up. I knew this meant another infection somewhere, and another trip to the E.R.

“Becca! Em! You kids are going to have to find a ride to the high school,” I called out. “Your dad’s got to go the hospital again.”

“Aw, Mom! Can’t you drive us on the way?”

I mustered that stern, guilt-inducing look that I imagined would silence them until their own anxiety took hold. Was there a better way to tell them that I needed them to grow up and parent themselves so that I could take care of their father? “Save it for therapy,” I told myself and bundled my shivering husband into the passenger’s side of his car.

My own remorse was beginning to gnaw on my conscience. I had spent the night hiding out in my college son’s empty room, Seagram’s gin in hand, crashed on a bare mattress, convulsing in tears and bitter anger, muttering aloud my rejection of the realities of my life.

“This is not right! This is not the life I deserve! Why have you failed me, God? Just make it all go away!”

In the master bedroom suite, Jim was already medicated with his 15 different evening prescriptions and hooked up to his nightly round of technological prophylactics: his insulin pump, his peritoneal dialysis machine, his CPAP (Continuous Positive Air Pressure) mask and the flat screen TV. His dark blonde head was propped up on several pillows, puffy blue eyes straining in a vain attempt to clear the haze of bleeding retinas. There was no way I could sleep with all that whirring and beeping and blinking of light. I wanted to slip into oblivion for just eight hours, escape the strain of appearing sane while chaos, stress and fear overwhelmed me. I figured that if I went into suspended animation and let time go by, things would have to be different when I surfaced. And different could be better. It could hardly be worse. I lay back and let the world spin.

We had arrived on the block 15 years earlier, The Golden Couple from California, high school sweethearts who married right out of college, refugees from the cinder block crack yards of Pomona, eager to raise our four above-average children in the economically stable Midwest. Our baby Emily had been hospitalized with bacterial spinal meningitis just a week before, but miraculously survived without a trace of brain damage. I unbuckled her from the car seat and held her up to see our new four-bedroom house. The moving van driver pulled up, squinted at the August sun, and looked around the neighborhood. “Good move,” he said wryly.

I thought we were finally safe, ready to live out our American dream unscathed. That winter while Jim was shoveling snow for the first time in his life, he felt pain radiating from his chest to his jaw. His doctor said “Mylanta”, but the cardiac stress test said total blockage in two main arteries. How does this happen to a 31-year old, tennis-golf-bowling athlete? We discovered he had diabetes and probably had had it for a decade or so. He had gained weight during our first year of marriage and during my pregnancies, but we never suspected anything. But again, we were saved from tragedy by open-heart, double-bypass graft surgery.

Jim had lived to see his children grow into troubled teenagers, and they had lived to see him grow sicker each day. Which was the cause and which the effect? And why had I failed to be able to pray another miracle into our life? Were we being afflicted for some extraordinary purpose? Driving to the hospital, I kept trying to make everything fit into a positive outlook suitable for our fairy tale life, but a nagging skepticism kept surfacing. We had lost our magic. We were no longer charmed. The dragons were winning, and I was mortally terrified.

Two days after my alcohol-induced escape, I rode the hospital elevator up to the fourth floor, cynically noting how routine the trip was becoming, how familiar and sad the décor seemed. I stepped into the room and saw Jim in the first bed with a tube sticking out of his neck. Betadyne colored the surrounding skin a bruise-like orange brown. Flakes of dried blood speckled the area. A dark-skinned male nurse was applying bandages to the wound.

“Oh, hi! You’re the wife, right?” he greeted me and began his instructions again. “Let me show you what we’ve got on him now. This is where he’s catheterized for hemodialysis. You can’t get this wet, so no showers while he’s using this port. Just sponge baths for a few weeks, okay? If the bandage gets wet or bloody, you’re gonna want to change it. Use gloves when you’re putting on the gauze, and cover it over completely with this plastic patch. These tubes can be taped together and then taped down on his chest like this. Careful of the caps. They unscrew to hook up to the catheter. If you take them off, you have to wear a surgical mask because, you know, this jugular vein goes directly into his heart. Any infection at this site is gonna travel swiftly in a life-threatening direction. Got that?”

I breathed deeply and felt as if I were still on the elevator, dangling by a cable. I then became aware that I had missed the last instruction.

“Um, hold on. I don’t think I heard that last bit. Actually, I’m suddenly not feeling too well. May I sit down?”

My semi-conscious brain was frantically sending warning messages. “This is not sustainable. You are not going to be able to keep him alive.” Jim’s ever-friendly and imperturbable countenance looked meekly on in an odd juxtaposition to this feeling of dread. It seemed like he could take any amount of medical abuse and be grateful for it. “Better living through technology,” he always said. I wanted to cry out, to interrupt this surreal charade, but I felt like I was under water. I realized we had no endgame and had avoided discussing it entirely. Platitudes and prayers were not addressing the issue adequately. Death. Mortality. It wasn’t supposed to be part of our story, and I was woefully unprepared. I blinked dumbly and swallowed.

“Okay. How do I do this?” I finally asked. The nurse blithely continued, never noticing that I wasn’t talking about the bandages.

© 2014, essay by Priscilla Galasso, All rights reserved

Wordless Wednesday

Leaf litter

This is the type of untidiness that needs not to be swept into piles and discarded in the gutter or collected in bags or cans. This is the dazzling detritus of Autumn, the fancy foliage of decrepitude; this splendid scattering of scarlet and gold makes sweet decay a glorious fate! Go ahead, Death, be proud! Come, decomposers, you fungi and millipedes, and create symphonies underfoot! Take a shuffling walk about this afternoon and breathe the perfume of change (if you’re not allergic!). Ain’t life (with Death included) grand?!

This is the type of untidiness that needs not to be swept into piles and discarded in the gutter or collected in bags or cans. This is the dazzling detritus of Autumn, the fancy foliage of decrepitude; this splendid scattering of scarlet and gold makes sweet decay a glorious fate! Go ahead, Death, be proud! Come, decomposers, you fungi and millipedes, and create symphonies underfoot! Take a shuffling walk about this afternoon and breathe the perfume of change (if you’re not allergic!). Ain’t life (with Death included) grand?!

Came home from work with a poem in my pocket…

Ever had one of those days? Decidedly moody, unable to focus, liable to shed tears at any moment. It started as I was driving in to work. By lunch break, I had a poem scribbled on the back of a museum map in my pocket. By afternoon break, I had texted my children just to tell them I missed their dad. Lovely souls that they are, they reached back immediately with cyber hugs. (thanks, kids!) So here’s the poem – no title came with it.

What can I do?

— it’s October

the sumac is red and my poor, backward head

is flooding nostalgia like liquid amber.

If I picked up guitar and a blues-country twang

— and sang

it’d be you in the sunshine

white overalls, your shirt as blue as your eyes

walking me home from school

sweet, musky sweat

your warm, solid arm

the newness of the world in the flash of your smile

— Hell.

Now 35 Octobers gone

I’ve aged like a maple leaf

Fall-ing, as once for you,

now with you, in spirit

falling, scattering, lifting

like ashes in a sunbeam

like milkweed in the wind

Shouldn’t I settle in the present? How can I?

— in October

when you’re long gone…

Weekly Photo Challenge: Focus

Focus. Concentrate. What is important? Who decides? And what about the other stuff? Again, photography acts as a metaphor for life. How do you get the experience of your own powers of creation? Make decisions, make art, and you know that you are making a universe. Then, unmake it, and you’ll know what you can control and change.

Is the glass half empty? Half full? Is the glass solid or as liquid as its contents but moving at a different speed? Am I half done with my life or beginning a new day? Are the things that exist only in my memory real or not? If they exist in my memory, have I lost them?

I had a birthday on Wednesday, and a good cry on Thursday. The quiet, summer afternoon transported me to another time and place. My husband was alive, snoring in the Lazy Boy in my living room. I had a living room – a full house with 4 bedrooms. My oldest daughter was in her room, reading children’s books. My son was in the yard playing with a next door neighbor. My two youngest daughters were entwined on a bed, thumbs in their mouths, damp curls encircling their sleepy heads. It seemed so palpable…and so untouchable. Never again; though, yes, it was. Once. LOSS loomed in my brain. A word I envisioned; I’d conjured it like the scene of that composite day. When I focused on it, I was awash in gut pain. It was powerful. Over moments, the focus softened. Its power faded. It became a muted background of warmth, of subtle longing, a wistful smile. There are other things in my life. Some embryonic, some ripening. That previous life is like the green light of a summer day. It is there, all around. It is not in focus, though. It is enough.

Honoring My Father (Reblog)

George William Heigho II — born July 10, 1933, died March 19, 2010.

Today I want to honor my dad and tell you about how I eventually gave him something in return for all he’d given me.

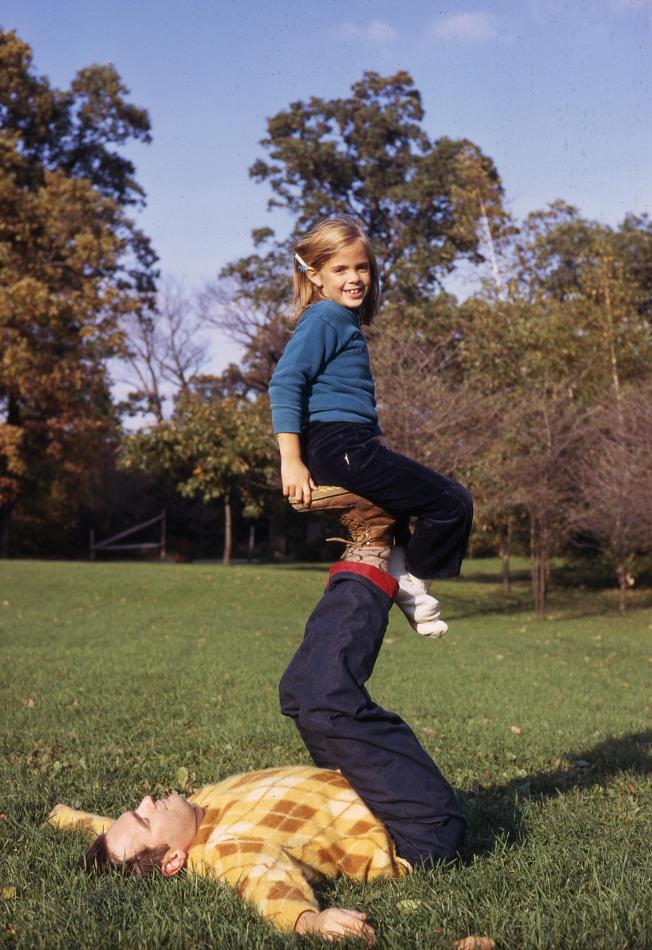

My dad was the most influential person in my life until I was married. He was the obvious authority in the family, very strict and powerful. His power was sometimes expressed in angry outbursts like a deep bellow, more often in calculated punishments encased in logical rationalizations. I knew he was to be obeyed. I also knew he could be playful. He loved to build with wooden blocks or sand. Elaborate structures would spread across the living room floor or the cottage beach front, and my dad would be lying on his side adding finishing touches long after I’d lost interest. He taught me verse after verse of silly songs with the most scholarly look on his face. He took photographs with his Leica and set up slide shows with a projector and tripod screen after dinner when I really begged him. He often grew frustrated with the mechanics of those contraptions, but I would wait hopefully that the show would go on forever. It was magic to see myself and my family from my dad’s perspective. He was such a mystery to me. I thought he was God for a long time. He certainly seemed smart enough to be. He was a very devout Episcopalian, Harvard-educated, a professor and a technical writer for IBM. He was an introvert, and loved the outdoors. When he retired, he would go off for long hikes in the California hills by himself. He also loved fine dining, opera, ballet, and museums. He took us to fabulously educational places — Jamaica, Cozumel, Hawaii, and the National Parks. He kept the dining room bookcase stacked with reference works and told us that it was unnecessary to argue in conversation over facts.

My father was not skilled in communicating about emotions. He was a very private person. Raising four daughters through their teenaged years must have driven him somewhat mad. Tears, insecurities, enthusiasms and the fodder of our adolescent dreams seemed to mystify him. He would help me with my Trigonometry homework instead.

I married a man of whom my father absolutely approved. He walked me down the aisle quite proudly. He feted my family and our guests at 4 baptisms when his grandchildren were born. I finally felt that I had succeeded in gaining his blessing and trust. Gradually, I began to work through the more difficult aspects of our relationship. He scared my young children with his style of discipline. I asked him to refrain and allow me to do it my way. He disowned my older sister for her choice of religion. For 20 years, that was a subject delicately opened and re-opened during my visits. I realized that there was still so much about this central figure in my life that I did not understand at all.

In 2001, after the World Trade Center towers fell, I felt a great urgency to know my father better. I walked into a Christian bookstore and picked up a book called Always Daddy’s Girl: Understanding Your Father’s Impact on Who You Are by H. Norman Wright. One of the chapters contained a Father Interview that listed dozens of questions aimed at bringing out the father’s life history and the meaning he assigned to those events. I decided to ask my father if he would answer some of these questions for me, by e-mail (since he lived more than 2,000 miles away). Being a writer, this was not a difficult proposition for him to accept. He decided how to break up the questions into his own groupings and sometimes re-phrase them completely to be more specific and understandable and dove in, essentially writing his own memoirs. I was amazed, fascinated, deeply touched and profoundly grateful at the correspondence I received. I printed each one and kept them. So did my mother. When I called on the telephone, each time he mentioned how grateful he was for my suggestion. He and my mother shared many hours reminiscing and putting together the connections of events and feelings of years and years of his life. On the phone, his repeated thanks began to be a bit eerie. Gradually, he developed more symptoms of dementia. His final years were spent in that wordless country we later identified as Alzheimer’s disease.

I could never have known at the time that the e-mails we exchanged would be the last record of my dad’s memory. To have it preserved is a gift that is priceless to the entire family. I finally learned something about the many deep wounds of his childhood, the interior life of his character development, his perception of my sister’s death at the age of 20 and his responsibility in the lives of his children. My father is no longer “perfect”, “smart”, “strict” or any other concept or adjective that I could assign him. He is simply the man, my father. I accept him completely and love and respect him more holistically than I did when I knew him as a child. That is the gift I want to give everyone.

I will close with this photo, taken in the summer of 2008 when my youngest daughter and I visited my father at the nursing home. I had been widowed 6 months, had not yet met Steve, and was anticipating my father’s imminent passing. My frozen smile and averted eyes are fascinating to me. That I feel I must face a camera and record an image is somehow rational and irrational at the same time. To honor life honestly is a difficult assignment. I press on.

Weekly Photo Challenge: Change

Pema Chodron writes in a book called “Comfortable With Uncertainty”:

According to the Buddha, the lives of all beings are marked by three characteristics: impermanence, egolessness, and suffering or dissatisfaction. Recognizing these qualities to be real and true in our own experience helps us to relax with things as they are. The first mark is impermanence. That nothing is static or fixed, that all is fleeting and changing, is the first mark of existence. We don’t have to be mystics or physicists to know this. Yet at the level of personal experience, we resist this basic fact. It means that life isn’t always going to go our way. It mean’s there’s loss as well as gain. And we don’t like that. …We experience impermanence at the every day level as frustration. We use our daily activity as a shield against the fundamental ambiguity of our situation, expending tremendous energy trying to ward off impermanence and death. …The Buddhist teachings aspire to set us free from this limited way of relating to impermanence. They encourage us to relax gradually and wholeheartedly into the ordinary and obvious truth of change.”